By John SudworthBBC News, Beijing

Merely reposting such images on Twitter – a banned platform not even accessible to most Chinese internet users – can get you detained.

A few months ago, I saw for myself the extraordinary lengths to which the authorities are prepared to go to ensure that Chinese citizens engage in absolutely no public discussion or visible acts of commemoration.

On China’s national tomb-sweeping festival – a time when people visit the graves of their loved ones – the BBC had arranged to meet an elderly woman whose son was shot through the head on the North side of Tiananmen Square, shortly after the first troops fought their way into the city.

Zhang Xianling showing a picture of her son to reporters in 2014

As she does every year, 81-year-old Zhang Xianling was planning to take flowers to the small, peaceful cemetery where the ashes of 19-year-old Wang Nan are interred, close to Beijing’s Summer Palace.

But we found the cemetery crawling with security guards keeping watch over the family memorial stone.

We were questioned by uniformed police officers who checked our passports and press cards, and took our details.

And Mrs Zhang was taken to and from the cemetery under police escort in order to keep her well away from journalists.

Mrs Zhang’s family grave, where her husband and son are burried

The BBC archive contains a compelling record of the events in which Wang Nan’s death played only a small part.

The video footage – every frame a testament to the bravery of those who filmed it – shows the soldiers advancing with weapons held at crowd height silhouetted against the burning vehicles.

And it captures the panicked protesters struggling on bicycles or on foot to carry the bloodied, bullet-ridden bodies to hospital.

But for me, one brief account in particular stands out.

‘They begged him to stop firing’

In daylight, sporadic bursts of gunfire can still be heard throughout the city and a visibly shocked British tourist, Margaret Holt, has found herself unwittingly caught up in one of the defining moments of the past century.

“This gun-happy soldier, he’s firing indiscriminately into the crowd and three young girl students knelt down in front of him and begged him to stop firing,” she says quietly, gesturing with her hands in a praying motion.

“And he killed them.”

She goes on: “An old gentleman put his hand up because he wanted to cross the road, and he shot him.”

In her late fifties or perhaps early sixties, and studying painting in a building just a few hundred yards from Tiananmen Square, Ms Holt points out of the window as she describes what happened to the soldier.

“The magazine of his gun was empty so he tried to reload and the crowd came in and hung him from a tree.”

The whole description takes just 24 seconds.

But its very brevity underscores the brutality of the force used to clear a peaceful protest, and the seething resentment of the crowds on the receiving end.

It also hints at why, even today, the authorities strive so hard to bury all discussion of what took place.

Winds of change

The protests that rocked Beijing and dozens of other Chinese cities in that spring and summer of 1989 were sparked – as is often the case – by an entirely ordinary event: the death in April of the previously sidelined Communist Party leader, Hu Yaobang, an economic and political liberaliser.

A spontaneous outpouring of public grief, led by students, quickly morphed into large-scale street demonstrations with calls for his reputation to be restored and for his legacy to be honoured with wide-ranging reforms: a free press, freedom of assembly, and an end to official corruption.

The Communist Party was split over how best to respond to the demonstrations

In Beijing, up to a million people poured into Tiananmen Square, occupying the vast public space at the political heart of the capital in a carnival of flags and banners and tents.

With the winds of change already blowing through Eastern Europe, in another chance piece of timing, the Soviet leader Michael Gorbachev arrived in Beijing in mid-May to take part in the first Sino-Soviet summit for 30 years.

To China’s leaders, as well as to the demonstrators on their doorstep, the country appeared to be teetering on the edge of a profound historical moment, and the Communist Party was split over how best to respond.

It was the hardliners who eventually won out.

Late at night on 3 June and into the morning of the next day, a full-scale military assault was launched on the square, with columns of tanks and soldiers advancing towards it firing live ammunition.

At intersections along the route to Tiananmen people refused to move out of the way and were mown down in a hail of bullets.

Some – as in the quote from the tourist above – fought back with their bare hands, and a number of armoured vehicles were reportedly set on fire by protesters using Molotov cocktails.

A burning armoured personnel carrier on 4 June 1989, near Tiananmen Square

Today, the ongoing secrecy and censorship makes it impossible to know how many died that night. No full, official accounting of the dead and injured has ever been made public.

The various accounts from the foreign journalists who were there, many of whom visited the city’s hospitals, suggest a broad consensus of anything from hundreds of dead to an upper estimate of around 2,000 to 3,000.

At least one diplomatic cable, written in the heat of the moment, gives a much higher figure.

What is beyond dispute is that it was a moment when a national defence force took on the role of an invading army in its own capital city, and a turning point that continues, in so many unspoken ways, to define China today.

Tank Man

Perhaps nothing illustrates the effectiveness of 30 years of Chinese censorship more than Tank Man.

On 5 June, the day after the clearances, a column of tanks was seen leaving Tiananmen Square along Chang’an Avenue where most of the killing took place.

Video footage captures a lone protester placing himself in front of the lead tank and then shuffling sideways each time it tries to move around him.

Tiananmen’s tank man: The image that China forgot

At one point the man, dressed in a white shirt and black trousers and holding two shopping bags, climbs onto the tank and tries to remonstrate with the crew through the turret.

For the outside world, this one iconic image – juxtaposing the authoritarian repression with the unquenchable spirit of defiance – has come to define more than any other what happened in and around Tiananmen Square.

It has also been pointed out that the tank commander – who cannot have known that the long-lenses of the international media were focused on the standoff – can be credited with showing some restraint.

Tank Man was not shot or run over but eventually bundled away to a fate still unknown to this day.

In China though, the image has been obliterated from public consciousness.

Inhuman crime

Today, Tiananmen Square appears largely unchanged from the video images of 1989.

Chairman Mao remains in pride of place, his pristine, slightly smiling face a continuing rebuke to the three protesters who threw paint-filled eggs at the portrait – and ended up serving jail terms of up to 20 years as a result.

But beyond the square China as a country has changed immeasurably over the past three decades.

As it grows ever richer and more powerful, that success might seem to offer the ultimate rebuttal to the acres of newsprint – these few paragraphs included – that insist that a dark, buried chapter of the past somehow still matters.

Bao Tong is a former senior official who had a ringside seat during the political upheavals of 1989.

He is now one of China’s best-known dissidents, having served a seven-year sentence, all of it in solitary confinement, as a result of his support for the Tiananmen protesters.

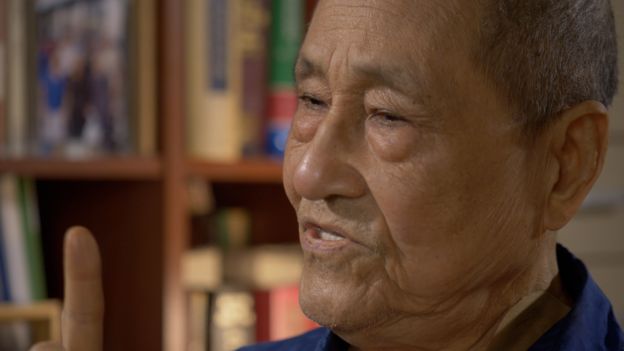

Bao Tong says China should allow people to discuss what happened in 1989

“What worries me,” he says, “is that in the past 30 years all Chinese leaders have been willing to stand alongside the inhuman crime of 4 June.”

Referring to the idea that China owes its current success to the crackdown, Mr Bao goes on: “They treat it as a valuable lesson, as a magic trick behind the nation’s rise. They consider it beneficial.”

“The CPC should allow people to discuss – victims, witnesses, foreigners, journalists who were there at the time. They should allow everyone to say what they know and figure out the truth.”

As if to prove just how vain a hope that might be, Mr Bao – who is constantly monitored and followed – was warned after our visit not to accept any more foreign media interviews.

But he is certain that if the protesters’ demands had been listened to all those years ago, China’s future would not only have been a prosperous one, but a more balanced and equitable one too.

“I see a China without a Great Fire Wall, without a privileged class. Unfortunately with less billionaires but at least the poor migrant workers could live freely without being driven out of the big cities. And a China that does not need to steal foreign technology.”

Power at all costs

The irony of the Tiananmen protests is that despite the sense of hope, when many truly believed change had come, they may instead have pushed back the chance of political reform in China for a generation or more.

Few of the students were openly calling for revolution – they would anyway have likely made poor leaders, riven as they were with factionalism, squabbling and autocratic tendencies of their own (as the best documentary made about the events makes abundantly clear).

But the Communist Party hardliners saw that even the more limited demands for rule of law and increasing democratic choice would spell the end of their absolute monopoly on power.

Had the protests never happened, had senior reformists not been silenced, purged or jailed, might China have followed the path of the other Asian states, Taiwan and South Korea, that had already begun their gradual, managed transition away from authoritarianism?

In China, no such reckoning is possible: An older generation is not allowed to remember, a new generation is not even allowed to know.

Instead, the decision that was taken is one that still holds fast today. The Party was going to hold on to power at all costs, and never again would a popular movement be allowed to try to loosen its grasp.

Thirty years on, the massive “forgettance” effort continues as forcibly as ever.

Original source: https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-china-blog-48455582

There are no official acts of remembrance for the events of 1989 in Beijing. But that statement, although factually correct, is far too neutral.

In truth, what happened in Tiananmen Square is marked faithfully each year by a massive, national act of what might more properly be called “forgettance”.

In the weeks leading up to 4 June, the world’s biggest censorship machine goes into overdrive as a huge dragnet of automated algorithms and tens of thousands of human expurgators cleanse the internet of any reference, however oblique.

Those deemed to have been too provocative in their attempts to evade the controls can be jailed – with sentences of up to three and a half years recently handed down to a group of men who’d tried to commemorate the anniversary with a product label.

Merely reposting such images on Twitter – a banned platform not even accessible to most Chinese internet users – can get you detained.

A few months ago, I saw for myself the extraordinary lengths to which the authorities are prepared to go to ensure that Chinese citizens engage in absolutely no public discussion or visible acts of commemoration.

On China’s national tomb-sweeping festival – a time when people visit the graves of their loved ones – the BBC had arranged to meet an elderly woman whose son was shot through the head on the North side of Tiananmen Square, shortly after the first troops fought their way into the city.

Zhang Xianling showing a picture of her son to reporters in 2014

As she does every year, 81-year-old Zhang Xianling was planning to take flowers to the small, peaceful cemetery where the ashes of 19-year-old Wang Nan are interred, close to Beijing’s Summer Palace.

But we found the cemetery crawling with security guards keeping watch over the family memorial stone.

We were questioned by uniformed police officers who checked our passports and press cards, and took our details.

And Mrs Zhang was taken to and from the cemetery under police escort in order to keep her well away from journalists.

Mrs Zhang’s family grave, where her husband and son are burried

The BBC archive contains a compelling record of the events in which Wang Nan’s death played only a small part.

The video footage – every frame a testament to the bravery of those who filmed it – shows the soldiers advancing with weapons held at crowd height silhouetted against the burning vehicles.

And it captures the panicked protesters struggling on bicycles or on foot to carry the bloodied, bullet-ridden bodies to hospital.

But for me, one brief account in particular stands out.

‘They begged him to stop firing’

In daylight, sporadic bursts of gunfire can still be heard throughout the city and a visibly shocked British tourist, Margaret Holt, has found herself unwittingly caught up in one of the defining moments of the past century.

“This gun-happy soldier, he’s firing indiscriminately into the crowd and three young girl students knelt down in front of him and begged him to stop firing,” she says quietly, gesturing with her hands in a praying motion.

“And he killed them.”

She goes on: “An old gentleman put his hand up because he wanted to cross the road, and he shot him.”

In her late fifties or perhaps early sixties, and studying painting in a building just a few hundred yards from Tiananmen Square, Ms Holt points out of the window as she describes what happened to the soldier.

“The magazine of his gun was empty so he tried to reload and the crowd came in and hung him from a tree.”

The whole description takes just 24 seconds.

But its very brevity underscores the brutality of the force used to clear a peaceful protest, and the seething resentment of the crowds on the receiving end.

It also hints at why, even today, the authorities strive so hard to bury all discussion of what took place.

Winds of change

The protests that rocked Beijing and dozens of other Chinese cities in that spring and summer of 1989 were sparked – as is often the case – by an entirely ordinary event: the death in April of the previously sidelined Communist Party leader, Hu Yaobang, an economic and political liberaliser.

A spontaneous outpouring of public grief, led by students, quickly morphed into large-scale street demonstrations with calls for his reputation to be restored and for his legacy to be honoured with wide-ranging reforms: a free press, freedom of assembly, and an end to official corruption.

The Communist Party was split over how best to respond to the demonstrations

In Beijing, up to a million people poured into Tiananmen Square, occupying the vast public space at the political heart of the capital in a carnival of flags and banners and tents.

With the winds of change already blowing through Eastern Europe, in another chance piece of timing, the Soviet leader Michael Gorbachev arrived in Beijing in mid-May to take part in the first Sino-Soviet summit for 30 years.

To China’s leaders, as well as to the demonstrators on their doorstep, the country appeared to be teetering on the edge of a profound historical moment, and the Communist Party was split over how best to respond.

It was the hardliners who eventually won out.

Late at night on 3 June and into the morning of the next day, a full-scale military assault was launched on the square, with columns of tanks and soldiers advancing towards it firing live ammunition.

At intersections along the route to Tiananmen people refused to move out of the way and were mown down in a hail of bullets.

Some – as in the quote from the tourist above – fought back with their bare hands, and a number of armoured vehicles were reportedly set on fire by protesters using Molotov cocktails.

A burning armoured personnel carrier on 4 June 1989, near Tiananmen Square

Today, the ongoing secrecy and censorship makes it impossible to know how many died that night. No full, official accounting of the dead and injured has ever been made public.

The various accounts from the foreign journalists who were there, many of whom visited the city’s hospitals, suggest a broad consensus of anything from hundreds of dead to an upper estimate of around 2,000 to 3,000.

At least one diplomatic cable, written in the heat of the moment, gives a much higher figure.

What is beyond dispute is that it was a moment when a national defence force took on the role of an invading army in its own capital city, and a turning point that continues, in so many unspoken ways, to define China today.

Tank Man

Perhaps nothing illustrates the effectiveness of 30 years of Chinese censorship more than Tank Man.

On 5 June, the day after the clearances, a column of tanks was seen leaving Tiananmen Square along Chang’an Avenue where most of the killing took place.

Video footage captures a lone protester placing himself in front of the lead tank and then shuffling sideways each time it tries to move around him.

Tiananmen’s tank man: The image that China forgot

At one point the man, dressed in a white shirt and black trousers and holding two shopping bags, climbs onto the tank and tries to remonstrate with the crew through the turret.

For the outside world, this one iconic image – juxtaposing the authoritarian repression with the unquenchable spirit of defiance – has come to define more than any other what happened in and around Tiananmen Square.

It has also been pointed out that the tank commander – who cannot have known that the long-lenses of the international media were focused on the standoff – can be credited with showing some restraint.

Tank Man was not shot or run over but eventually bundled away to a fate still unknown to this day.

In China though, the image has been obliterated from public consciousness.

Inhuman crime

Today, Tiananmen Square appears largely unchanged from the video images of 1989.

Chairman Mao remains in pride of place, his pristine, slightly smiling face a continuing rebuke to the three protesters who threw paint-filled eggs at the portrait – and ended up serving jail terms of up to 20 years as a result.

But beyond the square China as a country has changed immeasurably over the past three decades.

As it grows ever richer and more powerful, that success might seem to offer the ultimate rebuttal to the acres of newsprint – these few paragraphs included – that insist that a dark, buried chapter of the past somehow still matters.

Bao Tong is a former senior official who had a ringside seat during the political upheavals of 1989.

He is now one of China’s best-known dissidents, having served a seven-year sentence, all of it in solitary confinement, as a result of his support for the Tiananmen protesters.

Bao Tong says China should allow people to discuss what happened in 1989

“What worries me,” he says, “is that in the past 30 years all Chinese leaders have been willing to stand alongside the inhuman crime of 4 June.”

Referring to the idea that China owes its current success to the crackdown, Mr Bao goes on: “They treat it as a valuable lesson, as a magic trick behind the nation’s rise. They consider it beneficial.”

“The CPC should allow people to discuss – victims, witnesses, foreigners, journalists who were there at the time. They should allow everyone to say what they know and figure out the truth.”

As if to prove just how vain a hope that might be, Mr Bao – who is constantly monitored and followed – was warned after our visit not to accept any more foreign media interviews.

But he is certain that if the protesters’ demands had been listened to all those years ago, China’s future would not only have been a prosperous one, but a more balanced and equitable one too.

“I see a China without a Great Fire Wall, without a privileged class. Unfortunately with less billionaires but at least the poor migrant workers could live freely without being driven out of the big cities. And a China that does not need to steal foreign technology.”

Power at all costs

The irony of the Tiananmen protests is that despite the sense of hope, when many truly believed change had come, they may instead have pushed back the chance of political reform in China for a generation or more.

Few of the students were openly calling for revolution – they would anyway have likely made poor leaders, riven as they were with factionalism, squabbling and autocratic tendencies of their own (as the best documentary made about the events makes abundantly clear).

But the Communist Party hardliners saw that even the more limited demands for rule of law and increasing democratic choice would spell the end of their absolute monopoly on power.

Had the protests never happened, had senior reformists not been silenced, purged or jailed, might China have followed the path of the other Asian states, Taiwan and South Korea, that had already begun their gradual, managed transition away from authoritarianism?

In China, no such reckoning is possible: An older generation is not allowed to remember, a new generation is not even allowed to know.

Instead, the decision that was taken is one that still holds fast today. The Party was going to hold on to power at all costs, and never again would a popular movement be allowed to try to loosen its grasp.

Thirty years on, the massive “forgettance” effort continues as forcibly as ever.

Original source: https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-china-blog-48455582

Comments are closed.