Twenty-Eight Years After – An Interview With Wang Dan

Yaxue Cao sat down with Wang Dan (王丹) on September 27 and talked about his past 28 years since 1989: the 1990s, Harvard, teaching in Taiwan, China’s younger generation, his idea for a think tank, his books, assessment of current China, Liu Xiaobo, and the New School for Democracy. –– The Editors

WANG DAN. PHOTO: CHINA CHANGE

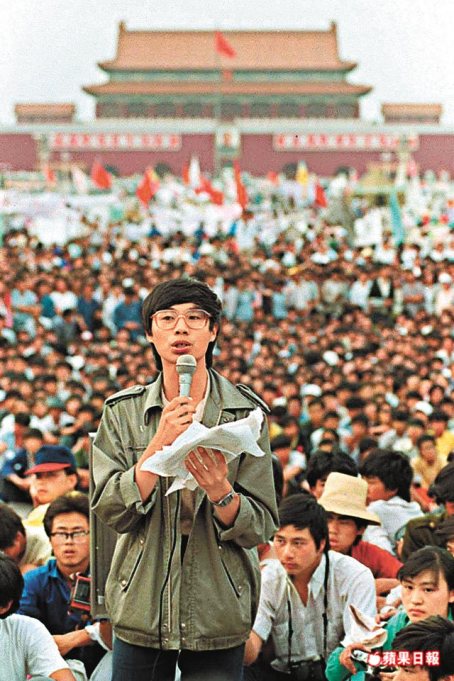

YC: Wang Dan, sitting down to do an interview with you I’m feeling nostalgic, because as soon as I close my eyes the name Wang Dan brings back the image of that skinny college student with large glasses holding a megaphone in a sea of protesters on Tiananmen Square. That was 1989. Now you have turned 50. So having this interview with you outside a cafe in Washington, D.C., in the din of traffic, I feel is a bit like traversing history. You recently moved to the Washington, D.C. area. I suspect many of our readers are like me –– the Wang Dan they know is still that student on the Square. Perhaps I can first ask you to talk a bit about where you’ve been and what you’ve been up to since 1989?

Wang Dan: When you speak like that, I feel that I have become a political terracotta warrior in other people’s eyes; when they look at me, they see only history. For me, 1989 is indeed a label I can’t undo. I’m conflicted about this label. On the one hand, I feel that I can’t rest on history. I don’t want people to see me and think of 1989 only, because if that were the case, it would seem that my 50 years has been lived doing nothing else. On the other hand, I am also willing to bear this label, and the sense of responsibility that comes with it. As a witness, survivor, and one of the organizers, this is a responsibility I cannot shirk. Everyone lives bearing many contradictions; this is my conflict, and all I can do is carry it.

After 1989, my life experience has been pretty straightforward. From 1989 to 1998, for a period of almost 10 years, I basically was in prison. From 1989 to 1993, I was in Qincheng Prison (秦城監獄) and Beijing No. 2 Prison (北京第二監獄); I was released in 1993. Then I was detained for the second time in 1995 on the charge of “conspiring to subvert the government.” During the period from 1993 to 1995, I was in Beijing starting to get in touch with friends who had participated in the student movement, and I also traveled all over the country. Deng Xiaoping went on a “Southern Tour,” I also took a southern tour. I started to assemble some of the June 4 student protesters. We issued some open letters, and started a fund to support political prisoners. We found more than 100 people to contribute, each person contributed ¥10-20 each month. The government said our activities were that of a counter-revolutionary group. This criminal charge was the same as Liu Xiaobo’s –– inciting subversion: writing essays, accepting interviews, criticizing the government. Because of these activities, I was detained again in 1995, but in 1998 I was sent into exile to the United States. Although I was out of prison for more than two years from 1993 to 1995, I had absolutely no freedom. Wherever I went, there were agents following me. The big prison.

YC: When you were released from prison in 1998, you hadn’t finished serving your sentence, right?

YC: When you were released from prison in 1998, you hadn’t finished serving your sentence, right?

Wang Dan: I was sentenced to 11 years in prison, but I only stayed in prison for 3 years. I was released on medical parole as a result of international pressure.

YC: At the time China needed acceptance from the international community, and it wanted to join the World Trade Organization. Now this kind of international pressure is impossible.

Wang Dan: After I came to the U.S. in 1998, in my second month here, I entered Harvard University. First, I attended summer school for a month, and then took preparatory classes for a year. I then studied for my Master’s degree and Ph.D. I graduated from Harvard in 2008. This was another 10 years, and this 10-year period was for the most part study. Of course, I also engaged in some democracy movement activities in my spare time. After graduating from Harvard, I went to England where I lived for a time, and then in 2009 I went to Taiwan to teach, which is where I have been living until this year, 2017. That’s eight years. So in the 28 years since 1989, I have either been in prison, studying, or teaching. During this whole time, regardless of what I was doing, I remained engaged in opposition activities.

YC: You were a history student at Peking University, and you studied history at Harvard. What would you most like to share about your 10 years at Harvard?

Wang Dan: Harvard has had a great impact on my life. I think with respect to China’s future, I have political aspirations, or a political ideal. I believe that China’s political future requires people who have specialized knowledge. So I feel a strong sense of accomplishment about getting my degree from Harvard. I achieved a goal I had set for myself. I think it is necessary preparation for my political future. This is the first point.

Second, at Harvard I was able to broaden my horizons. It gave me an international perspective. But obviously the most important thing, I believe, is my third point: the ten years at Harvard enabled me to just be an ordinary person. The students around me didn’t know who I was, only the Chinese students knew, but at that time there weren’t that many Chinese students. I was completely anonymous, just an ordinary international student. This was a very fortunate thing. If I were always only just a 1989 figure, active in the media, talking about politics every day, I’d feel really awful. During my time at Harvard, besides going to class, I also became friends with some people who had nothing to do with politics. It was just a very ordinary situation.

YC: Why did you go to Taiwan?

Wang Dan: Soon after I got to Harvard, I started to frequent the library. I saw a magazine called The Journalist (《新新聞》) –– a Taiwan magazine founded in 1987 focusing on social and political commentary. The Journalist covered the process of political transition in Taiwan after martial law was lifted in 1987. I was really excited reading it and began to be very interested in Taiwan. Later, I wrote my dissertation on Taiwan’s White Terror.

YC: Please tell us a bit more about your dissertation.

Wang Dan: This morning I was just talking with my editor, and we’re hoping that Harvard University Press will soon publish the English version. I compared state violence in the 1950s on both sides of the Taiwan Strait. At that time, Taiwan had White Terror, and China had Land Reform, the Campaign to Suppress Counter-revolutionaries, and the Anti-Rightist Movement, which was Red Terror. These are two forms of state violence, but each with different characteristics. What I was interested in was the different mechanisms, the specific methods by which it was carried out. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) used the method of mass campaigns. I analyzed how they were launched and executed. Taiwan’s White Terror was basically accomplished through political spying, with agents infiltrating society. When the National Security Bureau investigated so-called “communist spy cases,” they were mostly targeting individuals. The Kuomintang (the Nationalist Party) used agents to monitor society, whereas the CCP used the people to monitor each other. They turned everyone into a spy, including some of China’s famous intellectuals, who were also informants.

Back to your question of why I went to Taiwan. I went to Taiwan to teach –– there were no positions in the U.S. to teach Taiwanese history. Second, since my dissertation is a comparison of Taiwan and the mainland and Taiwan had started to democratize, I was interested in living there for a period of time so that I could experience it first-hand. Third, I really like Taiwan –– the scenery, the people, and the relationships between people.

YC: Please tell us more about your time teaching in Taiwan.

Wang Dan: I taught at pretty much all of the top universities in Taiwan, with the exception of National Taiwan University. I taught at Tsing Hua, Cheng Chi, Cheng Kung, and Dongwu –– mainly at Tsing Hua University, but also taught classes at other universities. After I arrived in Taiwan, I discovered a big problem –– they really didn’t understand mainland China. There were basically no courses at universities on contemporary Chinese history covering the period from 1949 to the present. So I decided to teach Chinese contemporary history, which is essentially what I taught during my eight years in Taiwan, in the hope that people in Taiwan would gain a better understanding of mainland China.

Another unexpected benefit was the arrival of mainland students to Taiwan. Shortly after I got to Taiwan, Taiwan opened its doors to students from the mainland. These students were 90-hou, the generation born after 1990. Before knowing them, I was just like a lot of people and looked down on them, believing they were a selfish generation, that they weren’t concerned with politics, that they were brainwashed by the government, and had absolutely no understanding of history. But after interacting with them, I discovered that this was a total misjudgment. They are in fact very idealistic, they really hope to change China. For example, in Taiwan I held debates on the issue of reunification versus Taiwan independence. I organized about 10 such debates, and each time there would be at least three or four students from mainland China who openly stated their names and university affiliation and said they supported Taiwan independence. There was even media covering these debates. This is really hard to imagine, isn’t it? I was really shocked. I asked the students if they were afraid of the media making this public, and one of them said, “If worse comes to worst, I go to jail, no big deal.”

Of course, not all of the 90-hou are like this, but I never really care about the makeup of the majority of any group. I believe that as long as a group has a few leaders, this country has hope. The students I came into contact with in Taiwan were inspiring, and gave me a morale boost. Previously I was pessimistic, and felt that even in 30 or 40 years it was unlikely that China would move towards democracy, but after engaging with the 90s generation, I became an optimist. I believe that I will see China change in the hands of this generation in my lifetime. And do you know just how fearless this generation of students is? They know who I am. There were some students who audited my class, but each semester there are quite a few students who directly selected and registered for my class. My name will appear on their transcript; they’ll take this back to China, and they just don’t care, they still choose my class. As of yet, there hasn’t been any instance of a mainland student being punished for taking one of my classes.

YC: Are you still in touch with them?

Wang Dan: I do stay in touch with some of them. There are a few who are studying for their Ph.Ds. in the U.S. And we have a Facebook group, and have become good friends. But I want to emphasize, it’s not all of the mainland students, but the mindset of at least 10% of the 90s-generation students whom I came into contact with in Taiwan is very forward looking. They’re more enthusiastic than us, and more eager for change. We thought these people supported the Communist Party, but it’s really not like that at all. I can say that 90% of them don’t support the CCP. I also think that this group of students is more resourceful than our 1989 generation of college students. I strongly believe that China will change in their hands. This is one of the reasons why I came back to the U.S., because I think there are more Chinese students like this in the U.S., students who are even more outstanding.

YC: What are some of the other reasons that prompted you to come back to the U.S.?

Wang Dan: Another reason is that I have been thinking about what I can do now. What’s my next step? I think that influencing the younger generation is one of the main things I can do. Of course, if history gives me the opportunity, I will throw myself into the democracy movement, run for office, even become president of China if possible. Why not? But I prefer to be the President of Peking University. But these things are unpredictable, and influencing the younger generation is something I can do right now. So whether I’m in Taiwan, or in America, I give talks wherever I can, to let the younger generation understand history; to let them know that we, as the opponents of the regime, are constructive and not just shouting slogans; and to let them know why China needs democratization to make the country stronger. I want the patriotic younger generation to know that if you are truly patriotic, you must oppose the CCP, and I tell them the logical connection between these two positions. During those years in Taiwan, in my spare time, on weekends, and in the evenings, I would hold “China salons.” I probably organized several hundred of these. The topic was very simple: get to know China. About half of the audience were mainland students, most listened without saying a word, nor asking questions. I felt it was OK, as long as they were listening. My responsibility is to pass the torch on to the next generation.

YC: I read your Tiananmen memoir, in 1989 you became a student leader, but before that, you got your start organizing democracy salons on campus.

Wang Dan: If you look at history, revolutions all start with salons. For example, the French Revolution got its start from salons.

YC: Let’s digress a little here. Can you talk a bit about the democracy salons you organized at Peking University?

Wang Dan: At that time, I was only a freshman; I didn’t have much experience. Liu Gang (劉剛) and those older guys were the first to hold salons. I followed after them. Each time we invited an intellectual, a so-called “counter-revolutionary,” to come. I hoped to use this platform to connect the ivory tower of the university with society.

YC: What kind of scale did you have? How many people attended each democracy salon?

Wang Dan: It could be as few as 20 or so people, but as June 4 approached, and the atmosphere was very tense, sometimes more than a thousand people came.

YC: Where were the salons held?

Wang Dan: Outdoors. We held one salon each week, on an area of grass in front of the statue of Cervantes, next to the foreign students’ dorm.

YC: Cervantes statue…. I like these details. It tickles the imagination.

Wang Dan: It’s a place where young students discussed politics and expressed their political views.

YC: I read that since you returned to the U.S., you’ve already held a few salons: in Boston, New York, Vancouver, and Toronto. How did these events go?

WANG DAN GRADUATING FROM HARVARD IN 2008. PHOTO: RADIO FREE ASIA

Wang Dan: Generally speaking, I feel that this generation is dissatisfied with China’s current situation. The fact that they left China to go abroad to study demonstrates that they are not that content, particularly those that applied on their own to go abroad. They are seeking new knowledge, but they are also quite confused. First, they don’t know what they can do. Second, they are disappointed in those around them; they feel that most Chinese they know are disappointing. Third, they don’t see any alternatives: who can take the place of the CCP? Because of these three issues, they are not able to express much enthusiasm. But in the process of chatting with them, I feel that there is a flame burning in their hearts. They really want to do something, to change things. When we talk about China, every person is critical. From the things they’ve said, it’s clear that they look at problems deeply; no less deeply than us. All of them have Ph.D.s or Master degrees. They are knowledgeable.

YC: Among the Chinese students studying abroad, many are the children of quangui (權貴), the powerful and the rich. They are beneficiaries of the system and tend to defend it.

Wang Dan: Not necessarily. In the early period of the Chinese Communist Party, many of the leaders were children of wealthy families. For example, Peng Pai was the son of a wealthy man in Shantou. The wealthier the family, the more likely they are to be inclined towards revolution, because they don’t need to worry about their livelihood, and they have more time to read and think. This is a possibility. Children from poor families have to think more about their livelihood, and have more to worry about.

YC: I feel I must disagree here: the powerful and rich families in China today are fundamentally different from the genteel class of traditional Chinese society.

Wang Dan: The parents of these families might be tainted, but the children are just a blank page. I’ve been in touch with some of these 20-year-old kids studying abroad, for example, children of mayors, and also chairs of the Chinese Student Associations who are in direct contact with the Chinese embassies and consulates. I don’t think the latter are spies. I’ve had quite deep conversations with them privately. They all know what’s going on. It doesn’t matter what family they’re born into, youth are youth, and young people have passion.

YC: I wish I could, and I desperately want to, share your enthusiasm. I admit that I have next to no interactions with children from quangui families. If there are rebels in their midst, it’s not showing. You look at today’s human rights lawyers, dissidents, and human rights defenders, people who are making efforts and sacrifices for a free and just China, you will see that the absolute majority of them come from the impoverished countryside.

Wang Dan: To the extent possible, I befriend young people from all different backgrounds born in the 90s. They are very smart, and they grew up in the Internet age. It’s not so easy for them to accept us as friends. But it’s very important to become friends with them. Some colleagues in the democracy movement are divorced from the young generation.

YC: So you believe one of your most important missions is to influence the young generation?

Wang Dan: Yes, one of them. In addition to salons, in the future I may organize summer camps and trainings. I’ve been involved in the opposition movement for so many years — what sort of look does the opposition movement take on in order to integrate with this era –– that is an important question. Starting from the time I was 20 until now, 30 years have passed, and what I have been doing politically is politics. For example, we have critiqued the totalitarian system, exposed abuses, rescued political prisoners, organized political parties, established several human rights awards, etc. I will continue to do these things, but now I feel that I’ve reached a time when I need to adjust what I’m doing; I want to somewhat remove myself from current, immediate events to think about what China will be like after the communist regime is gone. A lot of people are thinking about how to overthrow the CCP; I won’t be missed. The issue is this: if there comes a day when the CCP is toppled, regardless if it’s caused by other people or itself internally, what sort of situation will China find itself in afterwards? We need to have sand-table rehearsals. I’m interested in policies and technicalities for a democratic, post-communist China. Between politics and policies, I hope to devote some time and energy on the latter.

YC: That’s interesting and certainly forward-thinking. In the west, people are getting used to the idea that communist China is so stable that it will never fall. In any case, their plans are made based on such assumptions. But I keep thinking that the CCP hasn’t even stabilized something as basic as power succession.

Wang Dan: We need to have something like a shadow cabinet. We need to come out with a political white paper: how to conduct privatization of land; how to define a new university self-governance law. Obviously, this is a big ambition; it’s not something that can be done in a short amount of time. But this is the second big goal I set for myself after returning to the U.S.: I’m planning on establishing a small think tank to research and advance a set of specific governance policies.

YC: You didn’t leave China until the end of the 1990s, so you know the 90s well. Since the early 2000s, the rights defense movement has emerged, NGOs have burgeoned, and faith communities have expanded rapidly in both urban and rural areas, the entire social strata has changed as a result of the economy opening up. Previously, everyone belonged to a work unit, a “danwei.” Now a significant part of China’s population doesn’t rely on state-owned work units. They might work for a foreign enterprise or a private enterprise, or they might run their own small business or be engaged in other relatively independent professions such as being a lawyer. The rights consciousness of these people is totally different than before. I personally think they have been and will be the force for change because they are less subservient to the system. One may even say that they hate it, or they have every reason to detest it. What sort of observations do you have regarding the past 20 years in China?

Wang Dan: Profound changes occurred in China after 1989. First, never in the thousands of years of Chinese history has there been an era like today’s China in which everything is centered on making money—the economy takes precedence above all else. The second profound change is that in the entire country—from the elite strata to the general population—few have any sense of responsibility for the country or society. They’ve totally given up. From those in power to intellectuals to college students to average citizens, most people do not think that this country is theirs, they believe that China’s affairs are someone else’s business and that it has nothing to do with them. This is a first in China. I believe that these are two important reasons why China has not yet democratized. Therefore speaking from the perspective of the opposition, the most important task is the work of enlightenment. Those people who advocate violent revolution probably will oppose what I say, but I think Chinese people still need to be enlightened.

YC: I want to interject here that the fact that the elite class, whether it’s intellectuals or the moneyed class, have given up responsibility for the country is an indication of the rigor of communist totalitarianism. Isn’t that so? Hasn’t the Party worked methodically, meticulously, and cruelly to diminish individuals, including the elite class, into powerless atoms, preventing them from becoming a force, making sure they are beholden to the state, and depriving them even of a free-speaking Weibo (Chinese Twitter-like microblog) account? Having a citizenry that takes the country’s future into its own hand is at variance with the totalitarian system. It’s against the system’s requirement. On a personal level, acting out of a sense of duty for the country’s future is suicidal, it goes against one’s instinct for survival. Look at what happened to Liu Xiaobo and Ilham Tohti. Look at those lawyers who are tortured, disbarred, or harassed for defending human rights. Look at the professors who were expelled from teaching for uttering a bit of dissent. The Communist Party has a monopoly on China’s future as long as it’s in power, just as it does on the past and the present. Now please explain to us what you mean by enlightenment.

Wang Dan: For example, the majority of ordinary citizens sincerely believe that if China becomes a democracy, there will be chaos. Even if they have not been brainwashed by the CCP, even if they loathe Communist Party members, they still feel this way. Why do they think this? We need to reason with them. For example, just because the 1989 movement failed, it does not mean that it wasn’t the right thing to do. If you don’t talk about issues like these, the majority of people won’t think about them, therefore we must reason with them. This ability to inspire people through reason has a great potential to mobilize society.

YC: It was probably around the time of 2007 or 2008 when I first started looking at China’s Internet. There was also censorship, but comparing the Internet expression at that time to today, it was like a paradise back then, and there was a lot of what you call enlightenment, many public intellectuals or writers had many fans, and they could say and did say a lot. It was also around that time the CCP sensed a crisis, believing that if they continued to have lax control over speech on the Internet, their political power would be in imminent danger. Thus the censorship regime during the past decade has become stricter and more absurd. So now you are facing a very practical problem, even someone like Peking University law professor He Weifang can no longer keep a Weibo microblog account. People’s throats are being strangled, there’s no way for them to speak.

Wang Dan: Now it is very difficult, we must admit. But we shouldn’t give up just because some difficulties exist and sink into despair. Nietzsche said the disadvantaged don’t have the right to be pessimistic. You’re already underprivileged, if you’re then also pessimistic, your only option is to give up. I believe now is the darkness before the dawn. It truly is the most difficult time, but it is also the time when we have to persist the most. Like me, traveling around giving talks, oftentimes there aren’t many people at each talk, maybe 20 or so, but I feel it’s worth it.

YC: Liu Xiaobo died in a prison hospital. Even as someone who doesn’t know his work in any depth, I feel hit hard by it and it is difficult to grapple with. It’s like, for all these years, everyone sort of expected him to come out of prison rested and ready to go in 2020 after he served out his prison term. That’s not too far from now. When he died, it dawned on a lot of us that the CCP would never have let him walk out of jail alive. You were together with Liu Xiaobo in Tiananmen Square, and you worked with him during the 1990s, how does his death affect you?

Wang Dan: I grieve Xiaobo’s death as many others do. But I know that he would want us the living to do more. We need to do things that he can’t do anymore. And the best remembrance of Liu Xiaobo is to get more done and to see that his ideals for China become true.

YC: Many people won’t have the opportunity that I have to sit down with you. They know who you are, but they don’t know what you have been doing. They will say, “Those people who’ve been abroad all these years, what have they done? We haven’t seen anything!” How would you respond?

Wang Dan: First, I don’t really care about the various criticisms of me that others may make. I actually welcome it. It’s a form of encouragement, and at the very least, it’s a reminder. I personally feel I’ve done some things as I’ve told you. In addition, I’ve also come out with quite a few books that have made an impact.

YC: Could you tell us about your books?

Wang Dan: The book that’s sold the best is Wang Dan’s Memoir (《王丹回憶錄:六四到流亡》). And then there’s Fifteen Lectures on The History of the People’s Republic of China (《中華人民共和国史十五講》). Both were published in Taiwan, and both have sold well. The third book, titled 80 Questions About China (《關於中國的80個問題》), is the most recent. These 80 questions were all questions I encountered at the salons, so I packaged them together.

YC: What are a few examples of these questions?

Wang Dan: For example: Was Deng Xiaoping really the “chief engineer” of China’s reform and opening up? Why should we not place hope on a Gorbachev emerging from the CCP? Why hasn’t China’s middle class become promoters of democracy? In China, how does the CCP suppress opposition forces? Will democracy lead to social instability? Why don’t Chinese people speak up? Who are the people who might be able to change China? Why do we say “reform is dead”?

YC: While in Taiwan, you also founded the New School for Democracy (華人民主書院). What does it do?

Wang Dan: The New School for Democracy was founded on October 1, 2012. At the time, I wanted to advance the idea of a “global Chinese civil society” spanning Hong Kong, Taiwan, the mainland, Macao, Malaysia, Singapore, and overseas Chinese communities. Our Board of Directors are people from Hong Kong, Taiwan and mainland China. What we all face is the Chinese Communist Party. The CCP not only impacts the people of China, but also Taiwan and Hong Kong, and it influences the interests of Chinese all over the world, so I felt that we should all unite and combine efforts. We had an online course, and invited some scholars to give lectures. We later realized that there were not many people interested in a very specialized online course. A Salon was a major project of the school, and it is my contribution as chair of the Board of Directors. We also published a magazine, “Public Intellectual,” which we issued eight times before we had to stop due to lack of funding. Now that I have come back to the U.S., I hope to bring some of the school’s activities here, such as online classes, salons, trainings, and a summer camp.

YC: Your summer camp idea is really interesting. What would it look like?

Wang Dan: A summer camp that brings together students from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and mainland China who are studying in the U.S. They spend a week together, everyone becomes friends, exchanges views, and they have a better understanding of each other. They learn how to rationally discuss issues. No matter how controversial or sensitive our topic is, they must learn how to speak civilly. You can’t just curse another person because you don’t agree with something he or she said.

YC: On social media, I’ve seen so many people who lack the most basic democratic qualities although they ardently oppose dictatorship and champion democracy. They launch ad hominem attacks without making efforts to get the basic facts straight, and use the foulest language to hurl insults at people.

Wang Dan: So I think that one of the fundamental trainings is how to listen attentively to what the other person is saying, and to take care in how one says things –– to speak civilly and mindfully. There’s also some basic etiquette when speaking, such as not to interrupt others, etc.

YC: I think that’s about it. I hope you settle in smoothly, and that you’re able to start doing the things you want to do as soon as possible.

Wang Dan: It’s been eight years since I left the U.S. I can’t do the things I want to do all by myself. I’m looking forward to connecting with people in certain groups. First, Chinese students studying in the U.S.; second, Chinese living in the U. S. who are not engaged in the democracy movement but are concerned about democracy and politics; third, Americans who study China.

YC: Thank you. I wish you success in your work and life.