Liao Yiwu is a poet, writer and most recently the author of “Bullets and Opium: Real-Life Stories of China After the Tiananmen Square Massacre.” This piece was translated by Michael Martin Day, a professor at National University in San Diego.

On the night before June 4, 1989, the Communist Party of China launched an attack on its own people. With tanks and armored vehicles leading the way, as many as 200,000 troopsentered Beijing from several directions, surrounding Tiananmen Square, ramming, crushing and shooting unarmed demonstrators and causing hundreds, or thousands, or even 10,000 deaths.

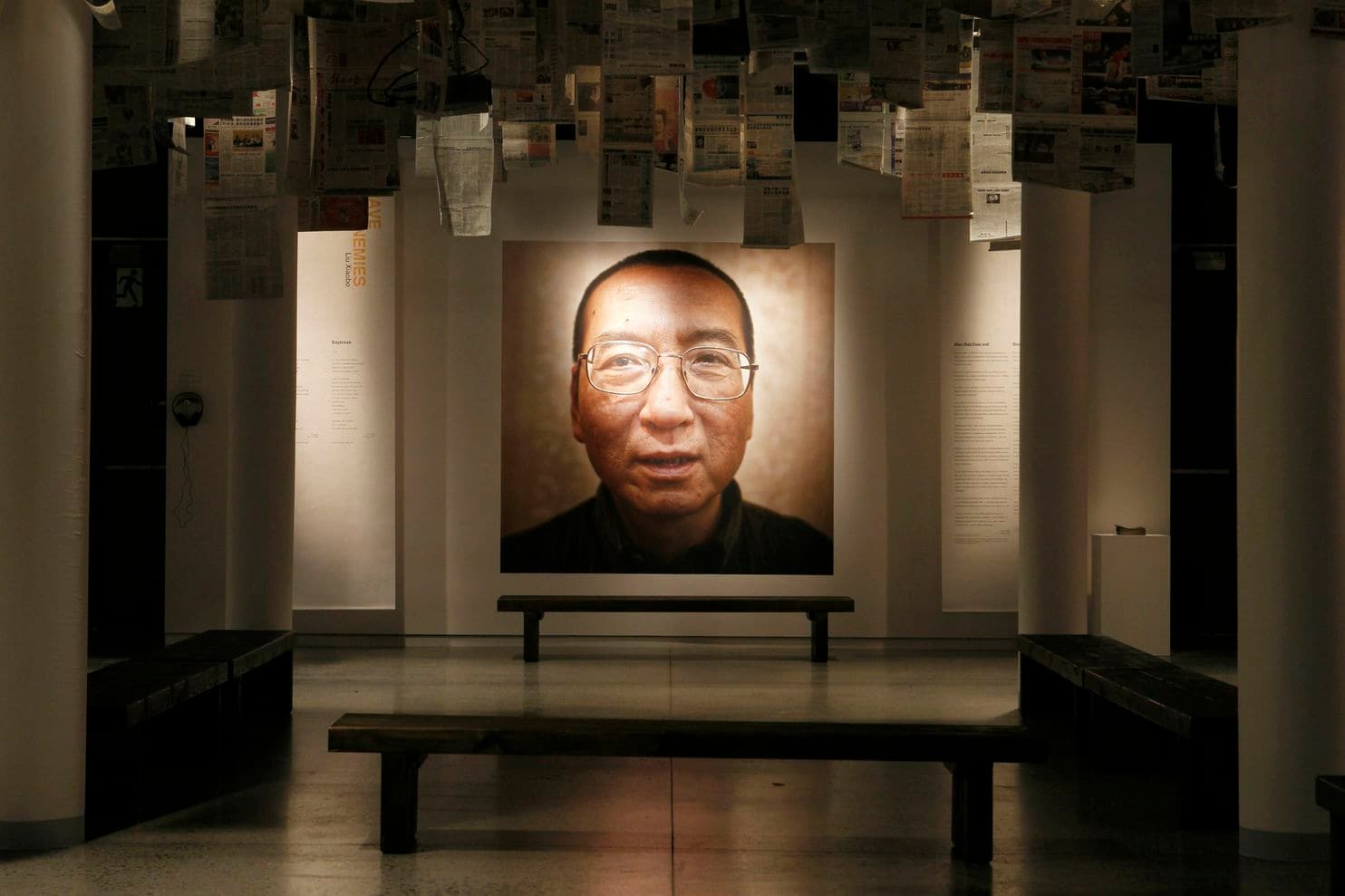

At the time, my dear friend, Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo, had returned from New York to join the pro-democracy movement. Though the killing had already begun miles away, he stayed with protesters, leading the crowd to destroy rifles left behind by troops that might have offered the steadily approaching soldiers an excuse to open fire.

The next day, in front of the Australian Embassy, Liu was invited to enter to safety. He hesitated for a few moments, but then declined the offer and rode away. He was later arrested and sent to Qincheng Prison. He survived the prison but succumbed to his father’s tearful entreaties and confessed, testifying against his will that he had not seen people die on the square.

After he’d been released less than two years later, he said, “Aside from lies, I have nothing.” From then on, his life was wrapped up in a theme of atonement. He drafted countless petitions and appeals. He helped the Tiananmen Mothers group. Each year, he wrote a long memorial poem. He was imprisoned four times and finally died in custody on July 13, 2017.

As I write this, two years after his passing, tears stream down my face. My life has been inextricably linked to Liu’s, and for both of us, June 4, 1989, was a turning point.

That day, I, who had previously refused all politics, composed the long poem “Massacre” about what happened on Beijing’s central square. Then, with the help of my Chinese-speaking Canadian friend, Michael Martin Day, I recorded myself reading the poem aloud.

The poem was circulated to many cities across China. After half a year of investigation, the police arrested me in Chongqing as I was about to flee. Many other poets and writers who had spread my poem were also arrested and imprisoned.

That year, China resembled a huge military camp, with people being arrested at train stations, on docks, on streets and in their homes. And even more people were in jail or attempting to escape. There were two great surges of exiles from China during the 20th century: 1949, when about 2 million refugees retreated to Taiwan after the civil war; and 1989, when political refugees smuggled themselves or were smuggled out of China — so many that “June 4th refugee” and “June 4th Green Card” have become key terms in the history of the Chinese diaspora. I was not a June 4th refugee — and neither was Liu.

I have so many memories of Liu, but indelible in my mind are the letters he wrote me — evocative, inspiring, tormented, resolute. More than 10 years after Tiananmen, he wrote:

Old Liao:

You torture me too much. Listening to your voice makes me wonder if my reasons for living are adequate. My tears flow into my heart, but after the tears, life still seems as shameless and frivolous as ever. People are dead, only the spawn of dogs can survive! Am I one? Are we? I pity myself too much.

A dog still has its dog nature; do Chinese people have a human nature? Between a person without humanity and a dog with a dog’s nature, the grace of the Creator must be bestowed on the latter. We’re not even on the level of dogs. Blood is nothing, betrayal is nothing, forgetting is nothing.

You sat in prison for four years because of this “Massacre,” and I think it was worth it. Prisons are more fit to comfort the last remaining tiny bit of conscience than one’s private self-blame and remorse. You really shouldn’t recite it with them. Your world has long been of a different sort, but they are normal and rational.

Living in shame, living for the blood of the innocent, is the only reason I can find [to go on]. The dawn of “June 4th” was the blackest and also the reddest day in my heart, and all the days and nights since June 4th have been neither black nor red. If shamelessness has a color, then it can only be this sort of color. What you can’t get past, you can never get past, even if one day we are able to comfort those innocent victims. But I still want to thank you and say to you in a near-extinct tone of reverence: “Thank you, my Baldy Liao!”

A letter from Liu written on Nov. 24, 1999

Letter from Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo to Liao Yiwu dated Nov. 24, 1999. (Image provided by Liao Yiwu)

I didn’t reply to his letter, because I didn’t know what to say. More than a month later, he wrote a second letter:

Compared to other characters caught up in the black curtains of the Communist Party, we can’t be called real tough guys. After so many years of great tragedy, we still don’t have a moral giant, like Vaclav Havel. In order for everyone to have individual rights, there must be a moral giant who sacrifices selflessly. In order to win a “negative freedom” (without the arbitrary coercion of power), there must be a will to actively fight.

History has no inevitabilities. The emergence of a martyr will completely change the soul of a people and enhance the spiritual quality of a people. [Mahatma] Gandhi was an accident, and Havel was an accident. The farmer’s child born in the manger 2,000 years ago was even more of an accident.

The elevation of man is achieved by these accidentally born individuals. We cannot place our hopes in the collective conscience of the public, we can only rely on a great personal conscience to bring together the cowardly general public. And our people in particular needs a moral giant. The emotional appeal of such a model is endless. Such a symbol would evoke a flood of moral resources. For example, Fang Lizhi [a Tiananmen protest leader who fled arrest] would have walked out of the U.S. Embassy, Zhao Ziyang would still have taken the initiative to resist, and Bei Dao would not have gone abroad. The reason for the silence and forgetting after “June 4th” is that a moral giant has not appeared among us.

Human kindness and tenacity are imaginable, but human evil and cowardice are unimaginable. Whenever a major tragedy occurs, I am shocked by human evil and cowardice. Conversely, I am calm in the face of the lack of kindness and resolve. The reason writing can be beautiful is that it can cause the truth to shine out in the darkness, and beauty is the rallying point of truth.

Excerpted from a letter written by Liu on Jan. 13, 2000

And so he went to jail and resisted, and resisted and went to jail, over and over. He took on the role of president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center and slammed the party and the government online daily. In 2007, he told me he wanted to personally award me the center’s Free Writing Prize. The plans were made, but, without warning, dozens of members of the Beijing PEN chapter, including Liu, were confined to their homes, and I was escorted to Sichuan by three police officers.

I didn’t know it at the time, but that was goodbye forever.

In the years that followed, he was sentenced, was imprisoned and won the Nobel Peace Prize. Then, with no warning, he was diagnosed with advanced liver cancer and hospitalized. I wrote: “I hope he comes to Germany. The most beautiful cemetery in Berlin is near my home. At its center there’s a lake where waterfowl fly. He can be buried here, and we could go to see him often.”

But the dictatorial regime wouldn’t release its grip, as though it feared even the ashes of this famous prisoner of conscience. A line from that second letter of his comes to mind: “The emergence of a martyr will completely change the soul of a people.” Three decades ago, the massacre completely changed his soul and mine.

Original source: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/07/12/liu-xiaobo-died-two-years-ago-honor-his-memory-read-his-letters/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.9a3ee8b4ceeb