The 19th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in October 2017 is sure to loom large in future accounts of China’s relations with the world. It was then that the party cleared the way for Xi Jinping to rule indefinitely, and when Xi himself advertised China’s global ambitions by declaring that Beijing would now “take center stage” in world affairs. It was also when Xi threw down the gauntlet in an equally consequential way.

In his three-hour speech to the assembled delegates, Xi extolled the virtues of Chinese authoritarian capitalism, and offered Beijing as a model “for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence.”

Xi’s speech, then, was not simply an announcement of China’s arrival on the global stage. It was a declaration of ideological competition — the starkest we have yet seen from Beijing — against the U.S. and the democratic community it leads.

In my last piece, I discussed how China’s expanding global military presence is posing new threats to U.S. interests. Yet as I argue in this ongoing series, there are multiple ways in which the challenge from a rising China has evolved in recent years.

Americans are used to thinking about China primarily as a challenge to U.S. global economic superiority and geopolitical primacy in the Asia-Pacific. What’s become clear, though, is that the ideological challenge an authoritarian China poses to democratic governance around the world is also quite serious.

Many observers have been slow to recognize that challenge, because any discussion of ideology is often dismissed as “Cold War thinking,” and because for so many years the free-market democratic model appeared incontestably dominant. Yet China is contesting that dominance, through a two-pronged offensive that involves promoting authoritarian governance while also undermining democratic practices in countries near and far.

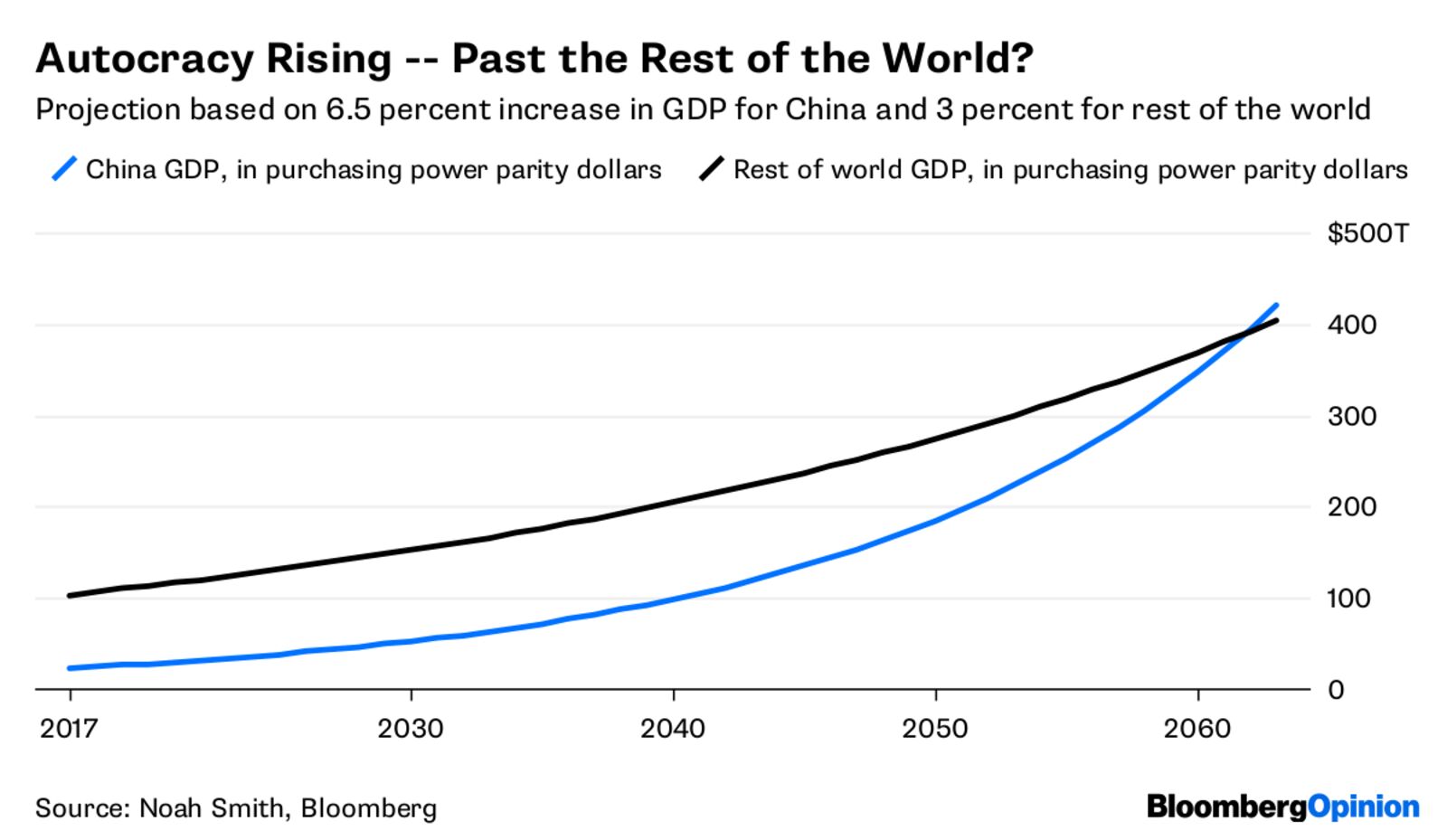

China’s ideological assertiveness has been building for years. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, pundits began arguing that the “Beijing Consensus” — the mix of state-directed capitalism and authoritarian political control — was displacing a Washington Consensus that had been badly tarnished by the near-meltdown of the global economy. A decade later, some projections have China on a path to dominating global GDP within half a century.

Thus it’s little surprise that China’s political-economic model has long seemed attractive to developing countries where economic growth is paramount and democratic institutions are often weak.

What has become impossible to ignore more recently is that China is actively working to fortify authoritarian governments around the world.

This should not be surprising. If the U.S. has long sought to make the world safe for democracy, China’s leaders crave a world that is safe for authoritarianism. The best way of achieving that goal is to ensure that China is not a lone, isolated autocracy in a democratic world. Autocracy-promotion thus becomes an ever-larger part of Chinese foreign policy.

In recent years, Beijing has lent its expertise on blending economic openness with tight political control to countries in regions from Southeast Asia to sub-Saharan Africa. It has exported the techniques and tools of repression — from riot control gear to tips on how to use the Internet to monitor and control dissent — to fellow authoritarian regimes. It has provided isolated dictatorships and backsliding democracies with crucial economic support and diplomatic cover, a recent example being Beijing’s backing for Cambodia’s Hun Sen as he has steadily pushed his country deeper into authoritarianism.

More broadly, China provides loans, capital and trade to autocracies and semi-autocracies as far afield as Angola and Venezuela, making them less dependent on Western sources of credit and commerce — and thus less susceptible to Western political pressure.

Chinese officials have also helped the autocracies of Central Asia guard against feared “color revolutions” that might spark ideological contagion within China’s own borders. Not least, Beijing has increasingly held up its own experience with authoritarian capitalism as an example for others.

To be clear, Xi’s China is not a crusading, messianic power in the style of Mao’s revolutionary regime, and China’s leaders would argue that they are simply conducting no-strings diplomacy in a way meant to be respectful of national sovereignty. But Xi and his advisers certainly understand that they will be safer in a world in which authoritarianism is more widespread, and their policies are working toward just that end.

This would be troubling enough for the U.S., were it not combined with the second prong of Beijing’s offensive — efforts to undermine the democratic systems of its geopolitical competitors.

As a spate of recent reports makes clear, China is waging a concerted campaign to mute international criticism of its politics and policies, and to render countries from the Asia-Pacific to Europe more receptive to Chinese influence. Because democratic societies are naturally resistant to such efforts when undertaken by a brutal, authoritarian regime, Beijing is using an array of tactics to manipulate open debate in these countries.

These tactics have included efforts to buy influence through political contributions and other payoffs in Australia and New Zealand, and the use of front organizations, propaganda organs and other mechanisms to shape public debate in ways that suit Beijing’s interests.

Beijing has also bullied foreign news organizations that report unfavorably on China, and sought to compromise academic discourse by giving preferential treatment to friendly scholars and using donations and other forms of economic largesse to shape the agendas of foreign universities and think tanks.

In Europe, the Chinese government has used economic leverage to punish countries that speak out against Chinese human rights violations and to reward those nations that stay silent. Even in the U.S., the Chinese government has underwritten nominally independent mouthpieces such as the Confucius Institutes that are present on many college campuses. There are also reports of Communist Party cells coordinating with Chinese students to push for curriculum changes that will portray China in a more flattering light.

In some ways, of course, these tactics are all part of the game of great-power politics. Yet more insidious in this case is that China is manipulating the open nature of democratic systems to distort public discourse, whether on human rights or Beijing’s behavior in the South China Sea. And when Beijing actively seeks to corrupt political actors or undermine the integrity of key social institutions, it crosses the line into political warfare against democratic systems.

The good news, from the perspective of the U.S. and other advocates of democracy, is that here as in so many cases Beijing’s growing assertiveness has engendered a degree of blowback. Support for corrupt dictators may endear Beijing to those rulers, but it hardly improves China’s image among the people they repress. Revelations of China’s influence operations in democratic societies have sparked concern and even outrage from Canberra to Washington.

But Beijing’s activities are nonetheless strengthening authoritarianism at a time when democracy is sagging around the world, and they are subjecting even established democratic systems to greater stress by clouding open political debate. China is waging the battle for the 21st century ideologically as well as economically and geopolitically, and the supporters of open societies around the world had best take note.